Diving Into the Cloud

January 4, 2012Is it any wonder that the forecast is calling for cloud? It’s a perfect storm out there, with powerful forces remaking the IT landscape in education. On one side, devastating budget cuts are pushing IT departments to identify ever-greater cost savings. On the other, the explosion in mobile devices is pressuring IT to provide anytime-anywhere computing with no downtime. And finally there’s data–a flood of never-ending data–that need to be stored and analyzed.

Implemented correctly, the cloud can help school districts tackle all of these issues. It promises to allow IT departments to support their institutions faster and more cheaply. But the term itself has become so abused that most people have no idea what "the cloud" means anymore. Right now, it’s more like a thick fog…

In this two-part series, T.H.E. Journal hopes to lift that fog and help IT administrators–and their constituents–understand the cloud, and what it can do to help districts ride out the storms buffeting their schools.

The easiest way to understand the cloud is to think of it as a utility, like electricity. When you plug a device into a wall outlet, electricity flows. You didn’t generate the electricity yourself. In fact, you probably have no idea where the electricity was generated. It’s just there when you want it. And all you care about is that your device works.

Cloud computing works on the same principle. Through a network connection (the equivalent of an electrical outlet), you can access whatever applications, files, or data you have opted to store in the cloud–anytime, anywhere, from any device. How it gets to you and where it’s stored are not your concern (well, for most people it’s not).

The potential benefits of such a system are enormous. To stick with the electricity analogy, if your IT department is still pre-cloud, it’s running the equivalent of its own generator. And with that comes a load of responsibility: Generators break, they run out of fuel, they need to be serviced, and–if demand for power increases–new ones need to be bought.

The cloud frees IT from the tech equivalent of all that. Because, just like power companies, cloud providers are the ones who are responsible for all maintenance, infrastructure, and repair. They are responsible for meeting surges in demand, and ensuring that service is reliable.

The analogy to electricity is a little simplistic, because cloud computing actually represents more than one type of service. Indeed, it might be more appropriate to compare cloud computing to all the utilities hooked up to your house: electricity, water, and gas. In the case of cloud computing, there are three basic types of service: software as a service (SaaS); infrastructure as a service (IaaS); and platform as a service (PaaS). At this point, PaaS is not used much in K-12 districts, so we will not describe it in detail.

Software as a Service

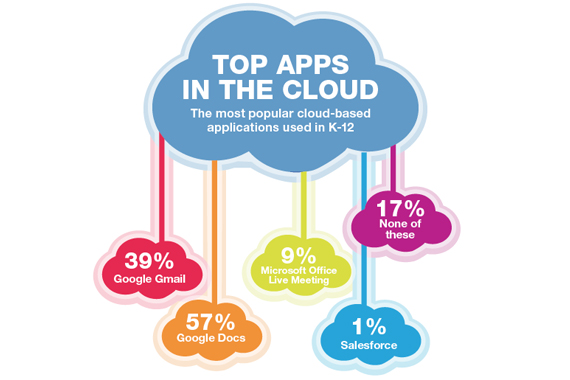

Ever used Gmail? How about Yahoo Mail? If so, you’ve used software as a service. In fact, many school districts have been using the cloud for a long time without ever quite realizing it. For some reason, web-based applications like these haven’t registered with most people as being "cloud." Only when applications like Google Docs replace software that has traditionally been locked inside the PC do people seem to realize it has something to do with the cloud angle.

Quite simply, SaaS is a software application that is hosted in a central location and delivered via a web browser, app, or other thin client (see box). Rather than having to purchase and install the application on individual computers, a school simply pays a monthly subscription fee to a service provider. Users–whether students or employees–just log on to access the application.

To the end user, the experience is exactly the same as if the application were installed on the user’s hard drive or the district’s internal network. By having the application delivered as a service, however, students can work on assignments from any location; HR managers can do payroll from the comfort of their living rooms; teachers can work on lesson plans after hours. What’s more, users can use different devices without having to tote around thumb drives to transfer information, since the project is all stored in the cloud.

And, from an IT perspective, there’s a beautiful upside: No longer do you have to update software on machines scattered throughout your schools. No more patches, no databases tracking installs and software updates. And the nightmare of keeping track of software licenses? Gone.

Most often, SaaS is associated with business applications such as accounting, customer relationship management, and human resource management, but more consumer-focused applications are coming online all the time. Google paved the way with its popular Google Apps for Education, which has been adopted as the de facto business productivity suite by a number of school districts.

In late June, Microsoft rolled out Microsoft Office 365, which includes a cloud-based version of its popular Office suite, in addition to its Exchange e-mail and SharePoint collaboration application. Although the cloud-based offering is not yet available for the education market, Microsoft does offer a similar suite of tools via the cloud through its popular Live@edu service. At some point, the company plans to transition Live@edu to the Office 365 platform, although a date has not yet been set.

Infrastructure as a Service

Think of IaaS as an outsourced data center with benefits. And limitless capacity. Storage, hardware, servers, and networking are all owned by a third-party provider that is responsible for the maintenance, operations, and housing.

Billing is handled monthly using the utility model (remember the electricity analogy?). Just as the electric company has a meter on your house to measure usage, cloud providers meter your computing usage–and you pay only for what you use. So, instead of buying a server that might run at 15-percent capacity, for example, you pay only for the 15 percent you use.

This pay-as-you-go model can provide a tremendous cost advantage for school districts, which see demand for computing power wax and wane over time. Instead of buying, maintaining, and housing servers to meet those periods of peak demand, schools can use the cloud to scale up or down as needed, without the need to purchase any hardware themselves. It’s more efficient.

In the K-12 space, IaaS hasn’t caught on as quickly as it has in higher ed, simply because most school districts haven’t needed the on-demand computing power that IaaS provides. However, as more districts find themselves needing to update their infrastructure to meet the goals of 21st century learning, IaaS may emerge as a way to shift their infrastructure upgrade from the capital expenses column to operating expenses.

Platform as a Service

PaaS is a term used to describe a software-development platform that is stored in the cloud and can be accessed via a web browser. It makes a variety of programming languages, operating systems, and tools available to developers, saving them the cost of purchasing and installing everything themselves.

It’s important to understand that each development platform is different. If an institution develops its application on a closed PaaS platform, there is a danger of vendor lock-in, since it may not be easy to migrate to a different platform.

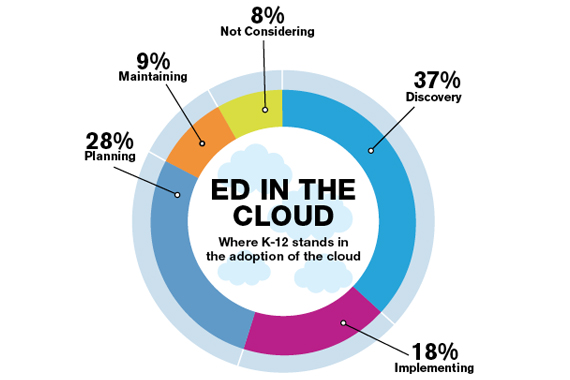

Source: CDW-G 2011 Cloud Computing Tracking Poll

Public Cloud

A public cloud is essentially what everyone means when they talk about "the cloud." As we discussed in "What Is the Cloud?" the infrastructure, applications, and resources are housed off-site in a location hosted by a third-party provider. Data is accessed via the internet on an on-demand basis, and users are billed monthly for their use of the resources within the public cloud.

The public cloud model has a number of benefits, including:

- Simple and inexpensive setup (the service provider incurs the cost of the hardware, applications, and bandwidth)

- On-demand scalability

- Users pay only for the resources they use

Because it is a public cloud, however, there are also some notable drawbacks, including:

- Greater risk of security breaches than with other cloud models. The business model of a public cloud is essentially based on economies of scale. It’s what allows cloud providers to charge low prices. For that to happen, most pursue a policy of multi-tenancy. In other words, the data of lots of companies and organizations will be stored in the same computing environment as yours. Although there is widespread disagreement about the risks involved, some people believe multi-tenancy increases the chances of breaches or accidental leakage.

- A perceived lack of control over data. Since the data is housed off-site and in someone else’s hands, schools don’t have physical possession of their own information, which makes some administrators nervous. And if the cloud provider’s system goes down, so too does your information, although the uptime of most cloud providers exceeds that of almost every in-house operation.

- Possible slow data transfer rates. Since public clouds use internet connections, the ISP controls the data transfer rate. School districts that want to use the cloud to store and transfer large amounts of data (high-definition security video, for example) may want to use a private cloud instead.

- A number of school districts are adopting software-as-a-service (SaaS) applications such as Google Apps that live in the public cloud. Others are using the public cloud to store and access nonsensitive data such as student assignments.

Private Cloud

For school districts that don’t want to surrender their data to what some perceive as the Wild West of public clouds, private clouds have emerged as an alternative. They can be managed by the school’s IT group or by a third-party provider, and they can be located either on- or off-site. In short, they offer the simplicity, flexibility, and elasticity of the cloud-computing model but for a single organization.

Sounds like a data center, right? Yes, but the way it’s set up is different. In a private cloud, virtualization of applications and resources is key. Through virtualization, private clouds offer easy scalability, flexible resource management (such as on-the-fly provisioning), and the most efficient use of the hardware. Other technologies work in tandem with virtualization, such as data center automation to help with auto-provisioning of servers and identity-based security to ensure that only authorized users have access.

Private clouds are an attractive option for districts that already have a properly functioning data center. In such cases, repurposing the data center can make a lot more sense than throwing it all out in favor of a move to a public cloud. If you decide to keep it in-house, though, just remember that IT is still on the hook for all maintenance and infrastructure.

Private clouds will also appeal to districts that worry that the public cloud may jeopardize their compliance with state and federal regulations, including the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and the Americans With Disabilities Act.

In K-12, private clouds are emerging as a way for school districts to manage heavy data loads while avoiding off-site storage costs. Additionally, a growing number of districts that provide computer-based learning are seeing the benefits of having their Windows, web, and hosted applications live in a central environment rather than on individual computers, because it offers secure access to the information from any location.

For example, the Florence Unified School District (AZ) is furthering its 1-to-1 computing efforts by centralizing its applications in a private cloud and providing access via the internet through an encrypted session to a virtual web desktop. The district worked with Dell and Stoneware, a private cloud software vendor, to develop the environment.

Hybrid Cloud

For schools wanting the best of both worlds, there’s the hybrid cloud. Hybrids are a combination of public and private clouds that offers the benefits of multiple deployment models. For example, an organization can couple its current on-premises hardware with cloud-based infrastructure that’s scalable and provisioned on demand, then place its applications and data on the best platforms and span the processing between the two. It’s a great way to capitalize on existing infrastructure while building in flexibility, scalability, and on-the-fly provisioning.

It also gives schools a way to address the whole security and privacy issue. You keep sensitive data–like student information–in the private cloud, while using the public cloud for less-important stuff.

Source: CDW-G 2011 Cloud Computing Tracking Poll

Of course, every great love is bound to have rainy days, and cloud computing is no different.

With a few exceptions, cloud-based application vendors tend to roll out updates to their services on a timeline of their own making. As Sarah Carsello, Minnesota Online High School’s systems engineer, points out, while that philosophy keeps her school on top of the latest releases of its critical software, there’s "an immense learning curve with constantly being on top of the new things that are available and the growing pains of trying to figure out how the changes will impact everybody." That includes, she notes, "being the first one to learn about bugs and issues and technical difficulties."

Also, users need to get used to trusting that their data is safe online. When it comes to backups, "People want to have that document on their own flash drive," explains Neil McCurdy, assistant principal at Coleman Tech Charter High School in San Diego. "They want to be making copies themselves." As he points out, "The data is a lot safer on Google, because it’s distributed and they’ve got people there making sure there are backups being done. They’re putting a lot more attention into making sure the data is safe than I could."

Of course, it doesn’t help that service outages take place even with cloud operations. While years of practice have helped IT people develop processes to follow in the event of down IT systems in the data center, they’re still learning what to do when a major cloud-based service goes down, as Microsoft’s Live@edu recently did.

"All of their data centers went down in North America," Carsello says. "We lost e-mail. We lost all of those services that we’re so reliant on. And we didn’t know how to communicate this to everybody, because the primary way we do that is through e-mail." As a result, she added, her school will need to develop processes to follow when a service goes down in the computing environment.

Gregory Partch hardly knows where to begin when it comes to the subject of how cloud computing saves his district money. The director of education technology for Hudson Falls Central School District in upstate New York might start with how he drastically reduced the number of servers he has to maintain. He might mention the lower electrical usage for PCs–or maybe the money he’s saved on software licensing costs. "We were able to eliminate $30,000 a year in software licensing costs for products that were not being used," Partch explains.

Cloud initiatives look better all the time to K-12 technology leaders because they offer the opportunity to off-load maintenance of services that are seen as commodities and free up IT staff to work on higher priority projects. They also may eventually allow districts to get out of the data center management business. But, as with any other application or infrastructure outsourcing, educational technology officers have to weigh potential risks and trade-offs and make a strong business case to their chief financial officers, superintendents, and school boards.

The business case will be different depending on whether you are moving infrastructure or just applications to the cloud. There may not be a huge cost savings if you are just moving from an upfront purchase to a rental model for software. Sometimes the assessment involves difficult apples-to-oranges comparisons, as in replacing a Microsoft Office suite with free Google Apps. "The free e-mail services are attractive options, but as the cloud matures you will have to keep reviewing the business decision and the types of control you are giving up," says Ben Marglin, a principal with Booz Allen Hamilton who specializes in IT strategy consulting for the public sector.

Many districts begin by adopting a hybrid little-by-little approach–maybe not zero servers to support, but fewer than today. "A school district may have a room with 150 servers in it," says Berj Akian, chief executive officer of ClassLink Technologies, a Clifton, NJ-based provider of K-12 cloud applications, including the instructional technology virtual desktop called LaunchPad. "But they say, ‘We are not going to keep adding to that. From here on, we are going to augment that in the public cloud.’"

As an example of that approach, Hudson Falls’ Partch says his first step–strictly speaking–was not cloud computing, but server virtualization with VMware and desktop virtualization with Citrix XenApp. That took the 2,400-student district from 70 physical servers down to 16 blade servers. It then replaced traditional PCs with 1,800 thin-client devices and created a private cloud environment.

Partch computed the annual cost savings in electrical usage alone at more than $47,000. "The thin clients cost much less, they have no operating system, and no moving parts," he says, and therefore much lower maintenance costs.

The cloud allows for use cases on a couple of fronts that look better when compared with traditional in-house technical infrastructure, says Akian. "Districts are realizing they can’t afford to be data center builders and owners. That is an unsustainable cost. The big cost saver is that the capital acquisition costs of hardware go away. Maintenance, manpower, electricity, and HVAC costs can be carved out."

Another option for districts not yet in a position to move everything to the cloud: private cloud consortiums in conjunction with other school districts. The Bloomington Public School District (IL) provides data center services and host applications for smaller nearby districts in a pay-as-you-go model. Launched in 2009, the nonprofit IlliniCloud provides disaster recovery, infrastructure as a service (IaaS), and software as a service (SaaS) to more than 100 districts in Illinois.

For the small districts, it is an easy business case to make. "If a school district needs a new server for special education, they could buy one for $6,000 or they could pay us $200 per year–a fraction of the cost," says Jim Peterson, chief technology officer for IlliniCloud. "We have people who are both athletic director and IT director for their small district," he says. "They don’t have the expertise or the budget, but they have the responsibility. With the economies of scale, this just gets cheaper as we get bigger."

In state departments of education that provide computing services to districts across the state, some officials have built strong business cases for using free and low-cost cloud offerings from Google and Microsoft. When the Kentucky Department of Education had trouble supporting e-mail across the state, Chuck Austin, product manager for Knowledge, Information, and Data Services, started talking to Microsoft about its Live@edu offering. "My CIO came to me and said, ‘Get me out of the e-mail business.’ It is high risk and low return," he recalls.

While the idea of saving money and streamlining IT operations in school districts is very attractive, administrators and IT professionals alike need to be aware that cloud computing is still an emergent technology, with some very real concerns and weaknesses that need to be addressed.

A) Security

In surveys of IT leaders, security is always the No. 1 reason organizations hesitate to either adopt or further implement cloud computing. Headlines like PC World‘s "Microsoft Cloud Data Breach Heralds Things to Come" in December 2010 are enough to give some technology executives second thoughts.

You have to do your due diligence about security, stresses Kentucky’s Austin. "You have to inspect their premises and security policies," he says. He explains that the state of Kentucky has a duty to require a degree of inspectability. "Upon an open records request, we have to have legal and technical capacity to inspect and open mailboxes, and we got that from Microsoft."

But Austin also believes there are myths about security in the public cloud. "People who are nervous about it and really want to keep that server under the desk with the lights blinking have to be aware that they always have security problems themselves," he adds, "with users forgetting passwords and keeping them on a sticky note on their keyboard."

Yankee Group principal analyst George Hamilton notes that "cloud providers don’t want to make their privacy policies public because it may invite hackers." But customers should turn to valid third-party audits such as ISO 27001 and the SysTrust audit. "You show me a cloud service provider that won’t open the kimono," Austin says, "and I’ll show you one I don’t want to do business with."

Private cloud consortia can bring certain security benefits to smaller districts. IlliniCloud’s Peterson says its members recognize that their data is actually more secure in the cloud. In the past they manually backed up data to tape in a time-consuming process. Now their data is backed up instantaneously each night in one of IlliniCloud’s three data centers located in different parts of the state.

Before migrating to cloud technologies, school districts should evaluate applications and infrastructure for vulnerabilities and ensure that security controls are in place and operating properly, says Booz Allen’s Marglin. He also suggests setting up an active monitoring program that uses services such as intrusion prevention, access and identity management, and security event log management to identify any security threats to the cloud implementation. Schools could turn to tools such as VMware’s Horizon Application Manager, which allows organizations to set up authentication and policy controls for SaaS applications. IT security executives can monitor who is using which application and can set granular policies about access.

Before contracts were signed, the Oregon Department of Justice had to make sure Google’s service met all federal guidelines and state statutes, including the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). Hamilton predicts that in a few years cloud storage providers will appeal to specific vertical markets, vowing to comply with whatever regulatory requirements apply to education, healthcare, etc. In the near term, of course, school districts will continue to operate in a heterogeneous environment, with some data on dedicated servers behind firewalls, some in private or consortium clouds, and some in public clouds.

Hudson Falls’ Partch says he would be somewhat reluctant to put any student demographic information or grades in the public cloud. "Everything like that stays on our side of the firewall," he says, "but student-created work and content is fine. We have 80 terabytes of storage, so there’s no need to use a public cloud for data storage."

Microsoft’s answer was Exchange 2010, hosted free with 10-gigabyte mailboxes for students and teachers. Kentucky had only been offering 5 MB for students, 50 MB for teachers, and 200 MB for administrators–not enough for some districts.

"We are providing Live@edu for 700,000 people, and we have full administrative control just as we do with an on-premise solution," Austin says. "We spent a lot of time kicking the tires before we moved to this platform. We were able to identify $6.4 million in cost avoidance with servers we don’t have to replace and software licensing costs."

Encouraged by the e-mail situation, Kentucky is moving Tyler Technologies‘ Munis financial system, used in all of its 174 districts, to the cloud by the end of next year. "We won’t have to do major software upgrades every three to five years anymore," Austin says. "We are out of that lifecycle management business. When Tyler upgrades Munis, we will just have it instantly."

The state of Oregon has had a similar positive experience so far with free Google Apps for Education. Initially planning to provide e-mail boxes for all students statewide itself, the Oregon Department of Education instead signed a contract with Google last year and now has 50 districts participating fully.

When the state began looking at providing student e-mail, it recognized that user management and support were going to be difficult. The staffing costs were going to be considerable to bring up 1,200 schools on virtual e-mail servers, saysSteve Nelson, chief IT strategist at ODE. "Looking at peer organizations, I made a conservative estimate that it would cost us $1.5 million," he says. Now students not only get e-mail, but also calendaring, online documents, video conferencing, and website creation tools.

He believes that the public cloud is not mature enough yet to place his district’s Windows applications there. "We like a hybrid environment. If a student brings his or her own device, it sees our network and we drop down a login screen for credentials. They connect to our private apps, but we can also provide links to public cloud apps through a single sign-on."

B) Contracts

School districts have been negotiating contracts for computing services now for decades. In many ways, negotiating the fine print on a contract for cloud computing services is similar to what those administrators have always done–but there are differences. Two experts on the matter agreed on one thing: It is important to sweat the small stuff.

According to Thomas Trappler, director of software licensing at the University of California, Los Angeles and an authority on cloud computing contracts, "You can’t walk away. With cloud computing, everything comes back to the contract."

Trappler and David Cottingham, senior director of managed services at technology products and services provider CDW, suggest four questions to always ask when working with a cloud computing services provider and four pieces of good advice.

Ask these questions:

- If you end up not being satisfied with the services you receive, how do you terminate the contract? Can you terminate for convenience or must you have cause?

- If there is a provider outage, what are you entitled to? Consider a service level agreement (SLA) for this that defines service terms, including how many hours and minutes the service must be accessible. If the provider fails to meet the SLA, what are the penalties or credits to be awarded to the district?

- In case of a catastrophe (for instance, a natural or man-made disaster) or major data loss, what are the provider’s contingency plans?

- Finally, what responsibilities do you have as a customer? For example, if a student or staff member uses an application or uploads a virus that damages the system, what is the district’s responsibility? In some cases, the provider’s acceptable use policy can shut your service down. If that happens, the district must have its own independent contingency plans to be able to operate in the meantime.

Follow this advice:

- Gather input first. Form a group of key stakeholders or subject matter experts that can review and evaluate the impact of a cloud service before it gets adopted. The membership of this group may vary depending upon organizational needs, but would typically include: the business process owner department, IT vendor management/IT procurement, IT technical, legal, IT security, IT policy, risk management, and audit/compliance.

- Describe–precisely–the level of service that will meet your needs. Spell out the parameters and definitions for each element of the service you expect, along with remedies for service levels that are not met. For example, information security standards will vary depending on what a certain department is doing with its data. Make sure you have all the information on your needs before you start negotiating with a provider.

- Trust, but verify. Check out the physical infrastructure of the provider’s facility. Don’t forget that your data still resides in a brick-and-mortar building. Where is the data center? Are there security guards and video cameras? Even if you’re moving to the cloud, there’s still a "there there" somewhere. Know where it is.

- Conduct due diligence. Some organizations, such as the Cloud Computing Association, are trying to establish cloud computing standards, but none of these is yet perfect. Nothing beats an old-fashioned investigation. And much of that involves (you guessed it) reading the fine print.

For more on the topic of cloud computing contracts, Trappler has written what may be the definitive article on the subject, "If It’s in the Cloud, Get It on Paper," available online.

C) Migration and Lock-in

Porting your data to a service provider is sometimes easier than getting it out. When assessing and managing the risk of cloud computing, you often hear concerns about "vendor lock-in." Given the relative immaturity of the cloud business model, some vendor shutdowns and acquisitions are inevitable. Therefore, school districts must have an exit strategy, a plan for moving data to another provider or back in-house if things go bad. Chief information security officers interviewed for this article suggest that contracts make clear that school districts are able to take their data elsewhere. Agreements should also require the vendor to delete all of the district’s data from storage media after handing it over, they add.

Of course, providing services again after eliminating hardware, software, and personnel is no small task. The state of Oregon worked out an agreement with Google that if the search giant ends the service it provides, the state would get five months’ termination notice. Austin says the Kentucky Department of Education’s legal representatives had to negotiate potential exit strategies with Microsoft. "They at first said they wanted to give us 30 days notice if they chose to terminate the service. We said it would take us a full year to stand it back up on premises," he says. "So they agreed to give us a year’s notice." With Tyler, the commonwealth had to negotiate and agree to stay with the service for a certain time period in order to get the cost it wanted. In turn, Tyler agreed to only raise the price a certain percent per year during that time period.

Having redundant vendors is a good idea whenever it’s feasible. When Amazon Web Services have had outages, some customers were just down during that time, while others had built-in redundancy, either with other Amazon servers or by automatically cutting over to other vendors.

Migrating from one infrastructure as a service vendor to another is definitely possible, but could be expensive and require consulting help from cloud experts.

The term platform as a service (PaaS) refers to a web-based development environment for cloud-based services. It offers enterprises access to shared, scalable IT resources on demand. But software developers building applications on a cloud platform such as Microsoft’s Azure Services or Google’s App Engine should look for the capability to port those applications from one vendor to another or move them in-house without having to rewrite them.

You might consider looking at open source options. In collaboration with NASA, Rackspace Hosting has launched OpenStack, whose development model is meant to foster cloud standards, remove the fear of proprietary lock-in for cloud customers, and create a large ecosystem that spans cloud providers.

Booz Allen’s Marglin says it is best to view public cloud services as you would a utility, so how much you can negotiate with the vendors may be limited. "You may not have a lot of choice," he adds, "but you should have your eyes open and always have a backup plan."

D) How to Plan

In spite of vendor promises to get you up and running in mere hours, early adopters have learned that undertaking a cloud initiative is like tackling any other transformational IT project in your organization. Therefore, it calls for the same basic script: Start small; work hard to prepare users for coming changes; learn as you go; continuously improve what you’re doing. And beyond that–prepare to improvise.

Cloud computing won’t necessarily stack up for every school district. You have to make sure you have a clear business case behind it. IT analyst firm Gartner sees two motivators that drive the exploration of cloud computing in education: "significant" cost savings–50 percent or more–and new capabilities, such as new forms of collaboration–like enabling virtual team meetings or sharing research data sets–that would otherwise be cost- or resource-prohibitive.

So build your case around a specific business problem you’re trying to fix, whether it is educational or organizational. Make sure that you’ve sized your choice to be appropriate to the level of cloud maturity your district or school has. If Gmail is the only exposure to cloud operations you’ve had so far, don’t move directly from that to shifting your student information system. Start with something in between, such as a service that delivers new functionality for a core group of users that have been clamoring for it.

Given concerns about security, control, and the financial and human resources changes that must be made, it makes sense to start with a small cloud implementation and build from there. Many districts begin with services that don’t involve sensitive data or much disruption.

Compare options for both keeping the particular operation or service in-house and moving it to the cloud. Attach expenses and savings to both columns–in-house and out-of-house–as part of the business case. Yes, cloud computing does entail startup costs, if only in moving data, managing system integration issues, and training people. Plus, there’s the hassle factor of making the shift. If you don’t understand these costs in full, they could wipe out any perceived savings. For example, if you’re moving to a cloud-based application, you may find that you not only have a subscription fee for the software you’ll be using, but you may also have a second bill each month from a hosting provider to cover the cost of hosting your software and data.

If you do determine that the cloud is the way to go, start moving that plan (and refining it as you go) up the line of management until you’ve attained senior sponsorship. Without administration buying into the plan and promoting it internally, commitment could buckle at the first whiff of user resistance.

Put Your Team Together

While you’re seeking senior leader support, get others involved too–the people in infrastructure, application development, security, principals, teachers, maybe even parents. All of them need to be informed and made aware of where cloud plans are headed. Plus, that shared ownership of the decision will come in handy as problems surface. (Consider it a bad omen if all fingers point to IT.)

Put together a dedicated cross-functional team to focus on the move to the cloud, with an eye to how some of these same team members, now with experience, can be shifted onto future cloud initiatives.

Work the evaluation of cloud vendors with the same taut structure as you would choose a new wireless provider. Create your scorecard, attach scoring criteria, and engage your community as much as possible in the assessment process.

Use an Experienced Negotiator

Be wary of vendor promises. They all claim to have the perfect solution. Right now, cloud providers are being bought up all over the place as large operators are consuming the smaller ones. Short of peering into a crystal ball, do the due diligence necessary to make sure they’re going to be around to support you–and, presuming they don’t stick around, find out how you’ll be taken care of in their absence.

Once you’ve selected a vendor, approach contract negotiations as if you were outsourcing the service. Bring in the purchasing person who has the most experience with service provider contracts, because much of the language and hidden gotchas will be similar.

Stay Involved

Finally, continually assess user satisfaction with the cloud service. Not only will this evaluation process let users know that you haven’t simply handed off oversight of their IT needs to some invisible technology god, but the results could reveal hidden benefits and deficiencies that will come in handy the next time you shift something to the cloud. After all, learning is the business you’re in.

The terms cloud computing and virtualization are often–albeit mistakenly–used interchangeably. Unfortunately, this perpetuates the idea that they refer to the same thing. They do not. If you’re confused, you’re not alone. Many people don’t know the differences between the two, so we’ve put together a concise overview that will help keep them straight in everyone’s minds.

Why the confusion?

Simply put, there are similarities between the two, and they are occasionally used for similar purposes. There are numerous articles and blog posts about helping consumers decide which better suits their needs–virtualization or cloud computing. But they aren’t mutually exclusive! You don’t have to have one without the other, and in many instances, virtualization that is hosted on the cloud or a cloud that provides virtualization might be a user’s best bet. The chicken or the egg, anyone?

At the forefront of the confusion are the attributes that virtualization and cloud computing share.

Both virtualization and cloud computing provide solutions that can:

- maximize use of computing resources

- add flexibility, agility, and scalability to management of computing resources

- manage multiple computers from a single source

- reduce the number of machines needed in a data center, thereby reducing:

- required space

- cooling systems

- staffing needs

- maintenance and hardware costs

But how–and why–they do these things is where the differences lie.

In its most basic definition, virtualization allows you to do more with less. Most computers aren’t used to their full capacity. In fact, far from it. Virtualization offers a way to combine the requirements of multiple machines into one, making use of unused computing resources.

Virtualization comes in many flavors: storage, desktop, memory, operating systems, servers. For example, server virtualization takes several independent, physical servers and puts them onto one machine. In a way, it’s like a mirrored fun house, tricking the system into believing there are more servers than there really are.

Virtual servers use less hardware, space, power, and even fewer cooling systems, in turn reducing hardware and administrative costs. Then, down the line, when the need for more server space arises, users can carve a virtual server out of the existing hardware, rather than going out and buying another machine. And the machine is being used much more efficiently than when each server occupied a separate machine.

The same principle can be applied to storage, desktop, memory, and operating system virtualization–the system fools the computer into handling multiple users’ needs on one piece of hardware–a useful feature for school districts or companies that need to manage multiple machines from one location or provide identical software or services to multiple users.

Cloud computing, too, has its variations: the type of service being provided, such as software as a service (SaaS), infrastructure as a service (IaaS), or platform as a service (PaaS). The same is true with the management and delivery systems: public, community, hybrid, or private. At its core, cloud computing can be defined as a resource for managing and delivering a service over the internet.

The quickly expanding reliance on cloud computing is in harmony with the growing impact mobile technology has on how people manage their lives. Devices like iPhones and iPads were never designed to run a standard operating system, nor to house applications. By necessity, apps that could run off of a remote server and be accessed through the internet became a way in which mobile devices could mimic the functionality of desktop computers, solidifying the value of cloud-based services. That same technology has found its way back to desktop computers (not unlike the hardwired user terminals employed by early personal computers), and now the cloud delivers applications over the internet without installing the software on the individual PC.

But the cloud, with its utility-based, on-demand model, has the added benefit of elastic scalability. Users can quickly and seamlessly gain more computing resources when needed and then drop down to fewer resources when they aren’t. And they only get charged for what they use. Computing resources in a public cloud are shared among all other users; with a private cloud, an enterprise has exclusive use of computing resources managed and held at a remote location, or the entire system can live on-site and within their own firewall.

It’s more than likely that virtualization is already in place on the servers used by most public cloud providers–although the end user would never notice, see, or even care. On the other hand, a private cloud would necessarily want to be virtualized, so that a company could more easily manage its resource pool. Both virtualization and cloud computing offer a more manageable system for the end user, but perhaps it’s by working in tandem that they can reach their fullest potential.

Forget the chicken and the egg. It’s more like chicken soup with rice. You can have the soup, or you can have the rice, but they’re both a little better when you have them together.